I wrote this a little after midnight on YELP:

I love sushi. Usually, I order from [. . . ]. I had missed lunch and it was getting close to dinner. [. . . ] could be delivered quicker than [. . .] so I tried it. The rice was both overcooked and soggy. I had a Thunder roll that I took one bite of and then gave up on. I tried two pieces of the California roll because how can you mess that up, right? I could not eat a third piece, it was so bad. I felt sick within 30 minutes and now, seven hours after eating it, I think I have finally thrown up for the last time tonight. Horrible. Will never order from it again.

Should I leave the review?

I have not yet. I still have it geared up and ready. Connecticut does not have a problem getting good sushi. But what if this was just a bad order? What if they normally do a solid job?

I do not know. I am posting it here while I continue to evaluate whether I should post it on YELP or (a) I give it a second chance or (b) at least ask around to see if anyone else has had a problem with it.

This is C.I.'s "Iraq snapshot

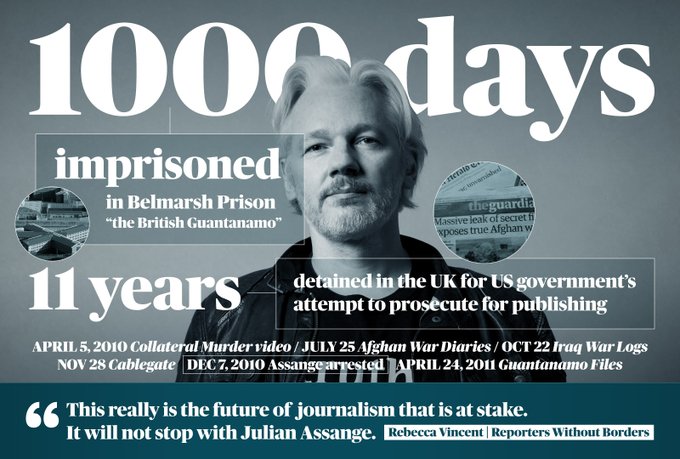

Julian Assange is the founding editor and publisher of Wikileaks, the pioneering transparency website. Wikileaks exposed U.S. war crimes in Iraq and Afghanistan, torture at Guantanamo and other abuses of power, releasing thousands of secret U.S. government and military documents that major news organizations worldwide, including The New York Times, The Washington Post and The Guardian then used as the basis for award-winning reporting. Assange is currently locked up in England’s maximum-security Belmarsh Prison, which has been described as the “British version of Guantanamo Bay,” as he fights the U.S. government’s attempt to extradite him on espionage and hacking charges. If extradited, he faces up to 175 years in prison if found guilty.

On Wednesday, activists marked Assange’s 1,000th day of incarceration at Belmarsh with a rally demanding his release. Prior to Belmarsh, he spent almost seven years inside the Ecuadorian embassy in London, under political asylum.

Among those protesting was Stella Moris, Assange’s financée and the mother of his two youngest children. “It’s really taking a toll on him,” Stella Moris said on the Democracy Now! news hour in November, speaking from outside the UN climate summit in Glasgow. “There’s no end in sight. This can go on for years, potentially.”

Stella Moris announced the 1000th-day vigil in a tweet that included an audio recording reportedly made inside Assange’s Belmarsh cell. Men screaming, guard dogs barking, and the incessant clang of metal doors slamming open and closed echo through the recording, painting a stark picture of the harsh conditions inside Belmarsh.

“The U.N. special rapporteur on torture has said that he is being psychologically tortured,” Moris continued. “His physical health has seriously deteriorated. They are killing him. If he dies, it’s because they are killing him. They are torturing him to death.”

Moris recently revealed that Assange had suffered a mini-stroke in prison on October 27th, the first day of his High Court appeal hearing. That court ultimately sided with the U.S. government, ordering that his extradition could proceed. Assange is currently seeking permission from that same High Court to appeal the ruling to the UK’s Supreme Court.

Threats to journalists and media workers worldwide have been on the rise. The Committee to Protect Journalists stated that, as of December 8th, 24 journalists had been killed in the line of duty in 2021, with eight more whose deaths may have been linked to their work. A record-breaking 293 journalists were imprisoned last year.

President Joe Biden opened his “Summit for Democracy” on December 9th, saying, “Free and independent media. It’s the bedrock of democracy. It’s how the public stay informed and how governments are held accountable. Around the world, press freedom is under threat.”

Biden’s words are true, but ring hollow as his Justice Department seeks to imprison Julian Assange for life, simply for performing those very functions of a free press that Biden praised.

“On the same day the Nobel Peace Prize honors journalists, a UK court ruled that the United States can extradite Julian Assange, a move that seriously damages journalism,” CPJ Deputy Executive Director Robert Mahoney said on December 10th, referring to Maria Ressa of the Philippines and Dmitry Muratov of Russia for their courageous reporting while under threat from their governments. “The U.S. Justice Department’s dogged pursuit of the WikiLeaks founder has set a harmful legal precedent for prosecuting reporters…The Biden administration pledged at its Summit for Democracy this week to support journalism. It could start by removing the threat of prosecution under the Espionage Act now hanging over the heads of investigative journalists everywhere.”

A coalition of 24 groups, including Human Rights Watch, the ACLU, the Freedom of the Press Foundation, PEN America and Reporters Without Borders called on the Biden administration to halt its Assange prosecution, saying it “threatens press freedom because much of the conduct described in the indictment is conduct that journalists engage in routinely—and that they must engage in in order to do the work the public needs them to do.”

Let’s talk about what is indisputable, who really was endangered and by whom.

The United States of America jeopardized the lives of Iraq’s entire 25 million people with an illegal and reckless invasion based on the lies that Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction and had direct ties to al Qaeda.

It’s indisputable that hundreds of thousands of Iraqi combatants and civilians were killed in the eight-year war because of violence and war-related causes. (Research in 2013 put the total at 400,000). It’s indisputable that four million Iraqis fled their country. Millions more were displaced internally.

It’s reasonable to say millions of Iraqis were wounded by violence or suffered illness from war-related causes. It’s fair to say millions of Iraqis will struggle with trauma and mental illness for life, that a countless number have already killed themselves.

American families suffered too: 4,431 U.S. soldiers were killed in the war and 31,994 wounded. Hundreds of thousands of American veterans have PTSD or moral injury, affecting millions of loved ones and friends. Same goes for any other foreigner who spent time in Iraq – soldier, security contractor, truck driver, cook, journalist.

And in case people think the Iraq War is over, Islamic State rose from its ashes. Yet no American government or military leader has ever been held to account for the lies and misrepresentations over Iraq. Meanwhile, the United States brazenly misrepresents the facts in its case against Assange with the blessing of successive Australian governments.

That’s why we need to make Assange’s freedom an election issue in Australia. It’s why we need to make noise on social media, in the mainstream media, to politicians, and on the streets. Because Assange is being tortured in a foreign country for telling the truth about the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. And he will be extradited to America where he will likely die in prison.

Remember — the Australian government eagerly took part in the invasion of Iraq. His case is the biggest test of press freedom in decades. Make some noise Australians! Bring Assange home.

According to the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, Assange has been arbitrarily deprived of his freedom since he was arrested on December 7, 2010. Since then he has been held under house arrest, confined for seven years in the Ecuadorean Embassy in London while he was protected by the administration of former Ecuadorean President Rafael Correa, and jailed in Belmarsh.

"The U.S. government is trying to put an Australian publisher on trial in a U.S. national security court, where he faces a 175-year sentence and imprisonment in conditions of torture and total isolation, simply because he was doing his job," Morris said. "He received true information about the victims and the crimes committed by U.S. operations in Guantánamo Bay, Afghanistan, and Iraq from Chelsea Manning, and he published it."

A veteran US diplomat says American forces are not leaving the Middle East in the near future despite Washington’s announcement of an end to its “combat mission” in Iraq.

Last month, the US announced an end to its combat mission in Iraq, but many Iraqi leaders have warned that nothing has changed in the number of American troops and the relabeling is a cloak to deceive the Iraqi people who are fiercely opposed to the presence of American forces.

In an article published by the Saudi-owned newspaper Asharq al-Awsat, Robert Ford, a former US ambassador to Syria and Algeria, said it was “ridiculous” to believe the US was leaving the Middle East, adding “the American forces are not leaving Syria and Iraq in the near future.”

“First, the Americans are keeping their bases in the [Persian] Gulf region in countries like Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. They are expanding the Muwaffaq Salti Air Base in Jordan. At the same time, the American navy continues to operate in the [Persian] Gulf and near the Arabian Peninsula,” Ford explained.

Second, he continued, neither of the former and current US presidents, Donald Trump and Joe Biden, withdrew all the American forces out of Syria or Iraq.

“In fact, the number of soldiers hasn’t changed for about two years and will not change much during the next few years. The Americans have promised not to undertake unilateral combat missions in Iraq and that is new,” the retired American diplomat pointed out.

The main political parties that won sizeable blocs in Iraq’s October 10 parliamentary elections are yet to reach agreements on power-sharing as the country’s parliament is scheduled to hold its first session Sunday.

After Iraq’s Supreme Court endorsed the results of the election, Barham Salih, Iraq’s President, on December 30, called on the new legislative body of 329 seats, to convene on January 9th.

Following the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 that toppled the regime of Saddam Hussein, it is a political tradition that the country’s three presidencies are shared among the three main components; the Prime Minister for the Shias, Speaker of the Parliament for the Sunnis and Iraq’s Presidency for the Kurds.

As time is running short, the Shia parties have yet to settle their disputes. Shia cleric Muqtada Sadr’s bloc, which has 73 seats, wants to establish a national majority government, and to sideline the pro-Iran militia groups gathered under the Shia Coordination Framework. But the latter have threatened to destabilse Iraq if Sadr were to try to marginal them.

According to Iraq’s constitution, in the first session of Iraq’s parliament, lawmakers must swear in a speaker and two deputies. To slip away from this constitutional obligation, however, it is expected that the session would be left open until all the sides would reach agreements to satisfy the different sides.

The disputes among the Sunnis and the Kurds on who will be nominated for the Speakership and the Presidency have not been settled yet. This is expected to delay the process of power-sharing, as the country faces crucial security and political challenges.

“Naming Iraq’s three presidencies would take some extra time,” Masaud Abdulkhaliq, a Kurdish political observer told The New Arab.